|

|

THE INDUSTRIAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION

AND THE FOUNDING OF TEACHERS COLLEGE

Grace Dodge was not only a passionately committed social reformer, she was

an enterprising one at that. Between 1880 and 1887, Dodge, who was gifted in

her ability to plan for the future, laid the building blocks for the

establishment of Teachers College.

It was only a few years after its founding in 1880 that Dodge and the group

of women who administered the Kitchen Garden Association (KGA) recognized that

the organization had outgrown its original philanthropic mission to teach poor

girls the fundamentals of domestic service based on a popular instructional

model of kindergarten education. In the context of the growing support of the

manual training movement among social reformers and leaders in education during

this period, Dodge orchestrated the redesign of the KGA, which was subsequently

renamed the

Industrial Education

Association (IEA) in 1884. Among other goals, the IEA aimed to provide

instruction in the industrial arts for both sexes and to make the industrial

arts (including the manual arts and the domestic arts) an integral part of

public education. Industrial Education

Association (IEA) in 1884. Among other goals, the IEA aimed to provide

instruction in the industrial arts for both sexes and to make the industrial

arts (including the manual arts and the domestic arts) an integral part of

public education.

Given the new objectives of the association and the broad resources required

to realize them, Dodge and her associates recognized the need for male support

and actively recruited men to participate in the administration and governance

of the IEA. While several prominent New York business and professional leaders

agreed to serve on the association’s Board of Managers, William Dodge,

Jr., Grace’s father, Frederick A. P. Barnard, who was president of

Columbia College and Seth Low, who was the mayor of Brooklyn, were made

honorary members. Alexander Webb, who was president of the College of the City

of New York, was appointed president of the IEA; though, Grace Dodge, who was

designated vice-president, assumed the active leadership role.

Dodge ably directed the IEA. Having grown up in a family that controlled

large, sophisticated business concerns, she learned to think in terms of growth

and expansion. Hence she made big, ambitious plans for the IEA, which,

supported primarily by donations and subscriptions, grew rapidly. The steady

rate at which the IEA expanded its programs and activities continually placed

the organization, in fact, in the position of searching for larger facilities

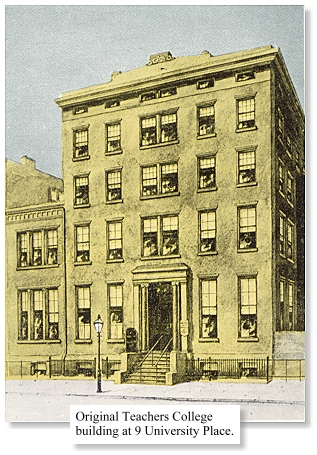

to accommodate its services. That came to an end in the summer of 1886 when

Dodge secured a permanent home for the IEA in the old Union Theological

Seminary Building at 9 University Place in Greenwich Village.

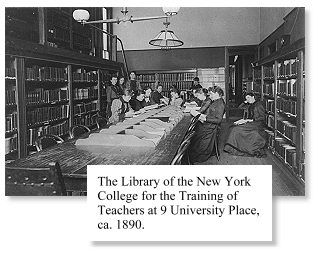

From its headquarters there, the IEA offered a wide range of services,

becoming in Dodge’s words, "a center of agitation, of information

and of organization." Among other activities, the IEA sponsored classes in

the industrial arts for public school children, training classes for teachers

in industrial education, public lectures on topics related to the manual and

domestic arts, and classes in the domestic arts for adult women. In addition,

the IEA functioned as a bureau of information about industrial education. It

published and disseminated articles about manual training and solicited and

organized information on the subject from sources across the country. According

to the association’s official reports, hundreds of people from all parts

of the country came to the offices of the IEA in search of information about

training in the manual and domestic arts.

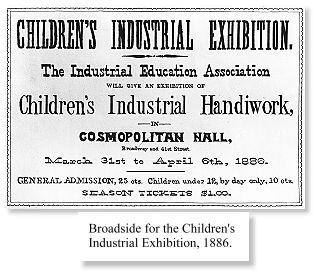

One of the association’s main objectives was to stir public interest

in industrial education.

With that in mind, the IEA

in 1886 sponsored the Children’s Industrial Exhibition at Cosmopolitan

Hall, on the corner of 41st and Broadway. A great success, the

exhibition, which, was open for seven days, received seven thousand visitors,

displayed work in industrial education from seventy different schools,

organizations and agencies in New York City and the surrounding region, and

attracted significant notice by the New York press. With that in mind, the IEA

in 1886 sponsored the Children’s Industrial Exhibition at Cosmopolitan

Hall, on the corner of 41st and Broadway. A great success, the

exhibition, which, was open for seven days, received seven thousand visitors,

displayed work in industrial education from seventy different schools,

organizations and agencies in New York City and the surrounding region, and

attracted significant notice by the New York press.

Among the issues discussed in the press was the fact that the New York City

public schools were not represented among the institutions displaying work in

the exhibition at Cosmospolitan Hall. Despite the success of the IEA’s

efforts to promote industrial education, the New York City public schools had

remained more or less indifferent to training in the manual and domestic arts

as a curricular innovation.

In an attempt to assuage public concern that the New York public schools

were not keeping pace with this trend in education, Mayor William R. Grace (who

had known Grace Dodge since she was a child) in 1886 appointed her and Mary

Nash Agnew, the wife of a Columbia College trustee, as the first female members

of the New York City Board of Education. Dodge served on the board for three

years, during which time she investigated the

maintenance of school buildings, made

recommendations for the adoption of textbooks, addressed inequities in the

salaries paid to female teachers, and avidly promoted industrial education. maintenance of school buildings, made

recommendations for the adoption of textbooks, addressed inequities in the

salaries paid to female teachers, and avidly promoted industrial education.

Shortly after her appointment to the Board of Education, Dodge, intent on

keeping the IEA on the cutting edge of reform, restructured the association to

support a shift in its goals and purposes. A shortage of trained teachers in

industrial education, a problem of immediate concern to the IEA and one it was

intent on helping to resolve, specifically reshaped the association’s

mission in terms more specific to the goals of public education. It was

abundantly clear to Dodge that the IEA had transcended its role as a

philanthropic reform organization. Feeling unqualified to lead the IEA at this

juncture, Dodge relinquished a good part of her executive duties, deferring to

the IEA’s new salaried president, Nicholas Murray Butler, who was

appointed in February 1887.

Butler, who, prior to his appointment to the presidency of the IEA was an

associate professor of philosophy at

Columbia College, had been preparing for a career in education, had

grand plans for the transformation of the IEA into a reputable educational

institution dedicated to the professional training of teachers and the study of

education. In line with his plans, the IEA soon evolved into the New York

College for the Training of Teachers, which, one year after Butler’s

resignation from the presidency in 1891, became Teachers College. In the years

following Butler’s resignation, Teachers College moved from its home at Columbia College, had been preparing for a career in education, had

grand plans for the transformation of the IEA into a reputable educational

institution dedicated to the professional training of teachers and the study of

education. In line with his plans, the IEA soon evolved into the New York

College for the Training of Teachers, which, one year after Butler’s

resignation from the presidency in 1891, became Teachers College. In the years

following Butler’s resignation, Teachers College moved from its home at

9 University

Place to a new campus, adjacent to Columbia University on Morningside

Heights, and Grace Dodge once again assumed a leading role in the institution

she had built from the ground up. 9 University

Place to a new campus, adjacent to Columbia University on Morningside

Heights, and Grace Dodge once again assumed a leading role in the institution

she had built from the ground up.

Return to ("Table of Contents")

|